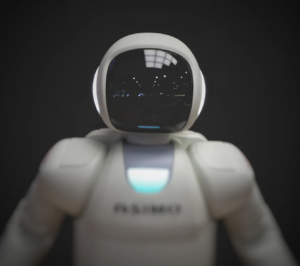

Our future with robots will force us to answer this question. In fact, the future is already here.

“I’ll be back.”

Add an Austrian accent, and you have one of the most iconic phrases of the sci-fi film canon, immediately evoking dystopian scenes of destruction from the humanoid robot, The Terminator.

Schwarzenegger’s robot franchise is not alone. Science fiction has provided a steady stream of futuristic robot lore over the last half century, encouraged not only by the rapid technological innovation that took place over this period, but also by the centuries of reflection on automatons that existed already. While the characters and plot lines vary, a common tension exists in almost all robot-related story-telling: how can robots and humans coexist?

As it turns out, answering this question isn’t just an exercise in imaginative screenwriting. Humanoid robots are already here and will be increasingly common in the not-so-distant future. As artificial intelligence (AI) continues to evolve beyond the need for human guidance, it is not difficult to imagine a world where every industry is disrupted by the emergence of autonomous humanoid robots.

The questions of science fiction are now the very real questions of the developed world: What will skilled laborers do when they are displaced by machines? Who will be responsible for accidents or injuries to human life at the hands of these machines? Further, what effect will the outsourcing of distinctively human work to increasingly advanced humanoid robots have on the value and dignity of human life?

According to Joshua K. Smith, it is time for evangelical Christians to begin considering these questions. In Robotic Persons, Smith points to three key areas where humanoid robots are likely to cause the biggest disruption in the near future: labor replacements, automated warfare, and sex/companionship. Each of these areas — work, war, and sex — will involve considerable human-robot interaction (HRI), surfacing significant challenges to current ethical, legal, and religious frameworks. Smith argues that evangelicals have the unique potential to bring clarity to these issues in a way that safeguards human interests and dignity. However, to establish such safeguards, evangelicals may have to reconsider their current understandings of humanness and personhood.

Should robots be granted personhood?

Smith’s primary argument is that evangelicals should join the fight to grant qualifying humanoid robots legal personhood. For Smith, this is not the same as granting AI-driven robots human personhood, as some have tried to argue. By virtue of humans bearing the image of God, Smith believes it is impossible for robots to ever qualify as equals with humans. Rather, Smith believes robots are created in the image of humans, not God. Thus, legal personhood offers a favorable solution for recognizing the moral agency of autonomous humanoid robots in a way that benefits everyone involved:

Personhood (and agency), in the eyes of current legal systems, is extendable to nonhuman agents such as historic sites, corporations, and other items of intrinsic or extrinsic value. The granting of legal personhood is driven by economics and not moral philosophy, which means it endeavors to protect property and promote innovation within the realm of corporate law. Arguments in favor of granting legal personhood is not solely about moral agency (i.e., historic sites will never be conscious), but protection. One might think about legal personhood as a firewall between corporations, inventors, engineers, coders, and the general public — it is about rights and responsibilities. (102–103)

In other words, granting robots legal personhood is not the same as granting robots human personhood. Smith side-steps the common questions of sentience and moral personhood as they relate to AI-driven robots. His argument is more nuanced, focusing instead on what legal steps might be necessary to promote human flourishing in the spread of humanoid robotics.

Smith suggests not only granting legal personhood to qualifying robots, but also advocating for a global code or regulator which would legally bind developers and corporations to innovate according to universally agreed-upon standards that protect human interests. Currently, no such legally-binding regulations for AI exist, and as Smith argues, it is not hard to imagine major corporations bypassing questions of morality in favor of economic expediency in future development. The question most frequently ignored in technological development is not, “Can we do this?” but, “Should we do this?” Legal personhood and regulations provide necessary accountability to protect human interests in the development process. These regulations are also grounded in the concept of tort law — the area of law dealing with liability in the case of harm or injury — which Smith demonstrates is something God cares deeply about, given the biblical evidence.

Essential to Smith’s argument is the notion that, in the absence of these legal protections, humans are likely to be devalued and objectified by other humans responsible for the design and implementation of humanoid robots, including those who lead major corporations. He argues that “the danger of dehumanization in the realm of robotics is that as it becomes economically feasible to replace humans in the realms of work, war, and sex, humans will lose their value and dignity in the site of humans, which will lead to multiple forms of objectification and damage” (164). Smith bases this claim on his understanding of human persons being created in the image of God.

Smith explores two fundamental understandings of the imago Dei in the book: an ontological view, and a teleological view. The ontological view (i.e., a focus on reason, sentience, consciousness, morality, etc.) is frequently behind the aversion many evangelicals feel towards discussing the personhood of non-human entities. But Smith doesn’t ground his argument in this view. Instead, Smith argues in favor of the teleological view, suggesting that bearing God’s image is not primarily to be like him in some metaphysical way, but to share a similar purpose or function (telos means “end”). According to Smith, humans are unique in God’s economy and “[t]he more humans desire to make a creature ontologically like them, and the more humans subcontract out their telos to robotics, the risk of dehumanization increases” (157).

A step in the right direction

Robotic Persons is a step in the right direction for evangelical thinkers who have, in many cases, fallen behind the pace of technological advancement in their analysis and assessment. Smith is right that evangelicals have a wealth of resources to bring to the discussion, particularly as it relates to the sanctity of human life. His argument also tempers the fear of doomsday prophets who proffer Terminator-esque visions of the future with humanoid robots, remaining optimistic about their potential while still realistic about the possible pitfalls.

By focusing on implementing practical legal regulations, Smith moves what could be a highly theoretical conversation into the realm of actionable knowledge, which is particularly helpful for evangelical readers new to the conversation. Further, in exploring the three industries of work, war, and sex, he is able to draw out specific and data-driven examples of the types of dehumanization he is concerned about, adding to the present-day urgency of his argument.

Smith deals well with a diversity of technical, legal, and biblical/theological material and will likely help readers of all backgrounds get acquainted with the proper introductory material. However, this breadth does mean that aspects of his argument were thin in places, and some assertions were made but not properly evidenced. One example might be in Smith’s claim that “the more robots become like humans, the less humans image God properly” (157). While he clearly demonstrates that introducing humanoid robots will result in dehumanization in a number of practical ways, it was not evident in his writing that the more human-like robots become, the less God-imaging humans will become.

Finally, this book would benefit from more judicious editing and perhaps even a rewriting for a less formal audience. It reads like a dissertation that was somewhat hastily formatted into a book, and as such is both overly formal and academic while also carrying a large number of formatting and spelling errors. The content of the book is both interesting and informative, and deserves attention, if the reader can look past these flaws in presentation.

If you are a Christian interested in our future with social robots, and want to go beyond the dystopian movies that populate our collective imagination, then Robotic Persons will be a helpful guide along the way. If you’re concerned about human dignity in the age of high technology, Smith offers a forward-thinking analysis with practical insights for how we might set up a future that honors God and his image bearers.

Gray Gardner (MLitt, University of St Andrews) is a pastor and leader focused on helping people think deeply about the intersection of faith and culture. His masters dissertation, “Pixelated Preachers: Simulcast Preaching and the Question of Embodiment in Multi-Site Churches,” was published in the Bible and the Contemporary World journal last year. Gray lives with his wife and three daughters in the Charlotte, North Carolina area, where he serves as a pastor at Forest Hill Church.

Read More from Gray: